Editor’s note: After this article was published, The Courier-Herald learned King County Superior Court Judge Chad Allred did not have access to Anthony Chilcott’s superform, which contained the Black Diamond Police Department’s official objection to Chilcott’s release.

Multiple safeguards meant to protect communities against the release of potentially violent criminals appeared to have failed in Black Diamond, when Anthony Chilcott’s release from King County custody led to his death during a police shootout on the Plateau.

But the factors behind Chilcott’s release may not be as cut and dry as they first appear.

Chilcott was arrested in late October and charged with malicious mischief, though the incident also involved him evading Black Diamond police officers and causing nearly $2,000 in damage to a patrol vehicle.

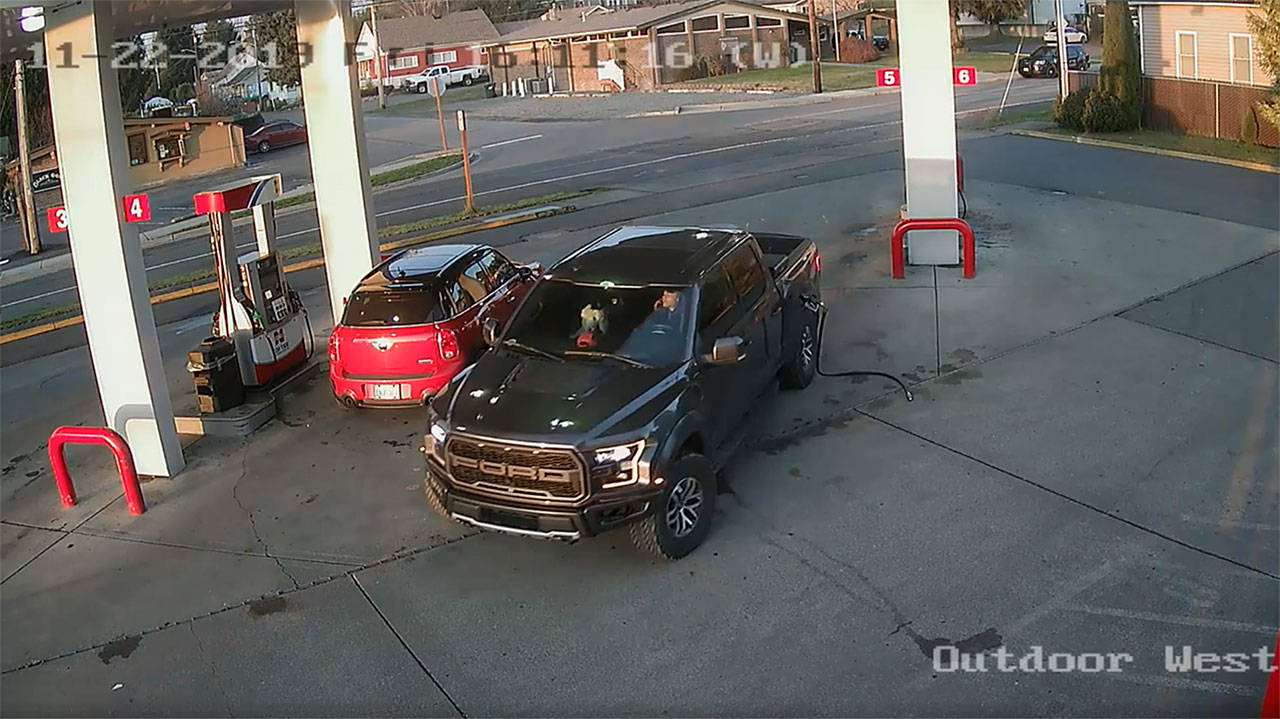

But despite the violence that surrounded his arrest, Chilcott was released on his own recognizance on Nov. 13, which in part led to his stealing of Black Diamond resident Carl Sanders’ truck at the Cenex gas station and the inadvertent abduction of Sanders’ 4-year-old poodle, Monkey, on Nov. 22.

Chilcott, the truck, and the dog were found by officers in Cumberland on Nov. 25 — the altercation ended with two King County deputies shooting Chilcott, who died at the scene. The details surrounding the shooting are still unclear.

After his death, many media outlets scrutinized Chilcott’s release by King County Superior Court Judge Chad Allred; why was a potentially violent suspect, who was already known to both the Black Diamond Police Department and the King County Sheriff’s Office for assaulting officers, resisting arrests, and failing to appear in court, released without bail?

CHILCOTT NOT LIKELY TO COMMIT ‘VIOLENT’ CRIME

Here’s a quick summary of Chilcott’s most recent arrest: Black Diamond police officers were called out on a welfare check on Oct. 28, and found Chilcott living on the property, with the permission of the homeowner. Chilcott attempted to evade arrest by taking off on foot, but was eventually caught by officers, who ended up using their Tasers to subdue him. However, after he was placed in a patrol car, Chilcott repeatedly kicked the car door, causing enough damage that the door could not be opened, and officers had to pull him out of the car to re-secure him.

Although Allred is ethically obliged to not discuss the case, King County Superior Court Presiding Judge Jim Rogers stepped in with a few explanations, offering insight into what Allred may have been considering during Chilcott’s case.

“Ultimately, the crime he was booked for was malicious mischief — he busted up a police car as he was being arrested. It’s like resisting arrest, but it’s more aimed at the destruction of the car,” Rogers said. “It’s a non-violent crime, because it doesn’t have any human victims… it’s more like a property offense.”

Black Diamond Police Department’s Cmdr. Larry Colagiovanni disagreed.

“He kicked out and did $2,000 to a patrol car. That’s violent,” he said. “Judge Rogers said this is a property crime. On the surface it is, but the circumstances resulting in the property crime were violent.”

Colagiovanni also said this was not the first violent offense Chilcott has committed, pointing to a July 2017 incident where he punched two BDPD officers while resisting arrest. However, the third degree assault charge, a Class C felony in Washington state, was dropped to fourth degree assault, a gross misdemeanor.

However, even assaulting a police officer may not be considered violent enough to hold a person on bail, or deny them release altogether.

Rogers explained that judges are bound to release suspects on their own recognizance unless the suspect is found likely to not show up to court, will likely commit a violent crime, or will likely intimidate witnesses, as is outlined in Washington Court’s Criminal Rule 3.2; violent crimes are defined as manslaughter, rape, kidnapping, arson, assault in the second degree, extortion, robbery in the second degree, vehicular assault, vehicular homicide, or any Class A Felony — none of which are on Chilcott’s record.

“What’s really important to realize from a judicial perspective is that the thing that Mr. Chilcott did — stealing a car with a dog inside, going on a high speed chase where he could have injured or killed somebody from the community, and then ultimately leading to his own death — … it’s hard to extrapolate that, in my view, from the crime of breaking up a police car or resisting arrest,” Rogers continued. “He had the information he had at the time, and it looked like a pretty low-level crime, considering the robberies and assaults and sexual assaults we see.”

But it’s unclear exactly how much Allred was aware of Chilcott’s record, given little of his criminal history was discussed during his arraignment. His attorney, David Bray of the King County Public Defenders Office and who represented Chilcott in the felony case, only recounted Chilcott had “a couple of misdemeanors, and that is his extent of his criminal history at this point,” while the prosecutor only focused on Chilcott’s most recent arrest, and not his prior assault charge.

Additionally, Allred did not have access to Chilcott’s superform, a document containing identifying information, a probable cause statement, and — maybe most importantly — the Black Diamond Police Department’s official objection to Chilcott’s release, stating Chilcott had a history of violence against officers and evading the law.

Colagiovanni said if the court had taken just a minute more to examine the case in front of it, Allred may have seen enough of Chilcott’s history to not release him on his own recognizance.

“In other words, if you look at his record, and you see an Assault 4 charge, that could be that he assaulted his neighbor, it could be a whole bunch of things,” Colagiovanni said. “But if they had just turned the page a little bit and asked the question, ‘What is this Assault 4 about?’ they would have saw that it was pled down from Assault 3. It was an assault of a law enforcement officer.”

Even Rogers agreed, saying Chilcott’s previous assault “should have been considered,” but added judges don’t often have a lot of time to ask those questions.

“We look at the cases beforehand, but again, Judge Allred on any particular day will have 30 to 50 cases in the morning, and between 70 and 150 cases in the afternoon that are on for scheduling,” he said. “Not all those cases take the same amount of time, so I don’t want to exaggerate that, but you’re on the bench all the time, hearing cases one after the other; you do prepare for them in the time you have, and we do that, but it’s a busy schedule.”

QUESTIONS ABOUT APPEARING, EMPLOYMENT

The other factor Allred had to consider when releasing Chilcott was the likeliness of him appearing at future court hearings.

“He would constantly fail to appear in court on the felony assault pre-charges for the officer, and King County Sheriff’s Office Fugitive Warrants Division was constantly coming into our department going, ‘Hey, we’re still looking for Chilcott. You know where he is?’” Colagiovanni said.

Bray said Chilcott’s previous failures to appear were related to his trouble finding permanent, stable housing.

“Mr. Chilcott was just getting some stability in his life,” Bray said, mentioning that he’s been in contact with Chilcott’s out-of-state sister, who was allegedly providing money to her brother in order for him to make it to court for future hearings. “He got a job at a restaurant, where he was working. He is unsure if that job is still going to be there for him when he’s released.”

As he was speaking, Chilcott can be heard beginning to sob.

“As the court can see, he’s relatively emotional because of how far he had actually come since I was last representing him,” Bray continued, ensuring the court that his client was not at risk of committing a violent crime and would do his best to attend all court dates if he is released from custody.

However, Colagiovanni doubted Chilcott was employed at the time of his most recent arrest.

“The testimony from the hearing was, he was working at a restaurant. That was not true. As far as I know — he’s been tooling around the city, we’d see him floating around — he didn’t have a job,” he said. “He worked at a restaurant a year ago, but he hadn’t had that job in probably close to a year.”

Bray declined to verify where Chilcott allegedly worked, or even if he simply confirmed Chilcott was employed, citing attorney-client privilege.

BLACK DIAMOND JUDGE ALSO RELEASED CHILCOTT

Though initial coverage of this story focused solely on Judge Allred’s decision to release Chilcott without bail, he was not the only — or the last — judge to do so.

Before his arrest on Oct. 28, Black Diamond Municipal Judge Krista White Swain signed a bench warrant for Chilcott’s arrest on Oct. 25, for failing to appear for a criminal trespass charge from December 2018.

After Allred released Chilcott from King County custody on Nov. 13, he was transported to the Enumclaw jail, where the city of Black Diamond requested a bail be set at $2,500 for his failure to appear.

However, Swain released Chilcott on his own recognizance on the condition that he supply a current mailing address.

He used his cousin’s address, though his cousin was unaware he had done so, and said they were not in contact in recent months. She also said it was common for family members to use her address to send mail to, as the home used to be their grandmother’s.

Swain declined to comment on her decision to release Chilcott.