Talking publicly about your body is not high on most teenagers’ wish lists. For Buckley teen Ella Roehr, there wasn’t another option.

For most of her life, Ella has had trouble eating and maintaining a healthy weight. Pain in her stomach, vomiting, dizziness and blurry vision followed her everywhere, especially when she exercised. Her health problems became especially pronounced around elementary school, and the pain became so great that she couldn’t eat solid foods for two years.

Classmates would say things like “go eat a burger” or “try some food,” Ella said, and by middle school, many of them assumed she was anorexic.

But she wasn’t suffering from an eating disorder. Ella, now 17, had Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS), a condition in which connective tissue in her chest area compressed a major artery and the nerves surrounding it. It caused excruciating pain, especially when she ate, and starved many of her organs of the blood they needed to function.

Things are different now. After years of work to learn about her illness, Ella finally received the surgery to correct her MALS in August. Eager to get the word out and help other young people like her, she interviewed for and successfully became Miss Pierce County Teen last spring, and this weekend, the White River High School senior is competing to become Miss Washington Teen.

But years ago, young Ella and her family didn’t have the four-word name for her condition. They just knew she was in pain, sick with a condition that eluded understanding.

“Many doctors compare the pain of this to pancreatic cancer,” Ella’s mom Annie Roehr said. “To see that kind of pain in your child, it kills you.”

In 8th grade, a classmate told Ella she should start going to the gym to gain some weight.

“I know the girl meant it innocently, but it really stuck with me,” Ella said.

And “that was a point where I realized people didn’t understand that I was sick,” she continued. “If you look at your classmate who’s 5’4’’ and 70, 80 pounds, there’s no other conclusion you can go to. I realized, if I’m not going to talk about what’s wrong with my body, no one’s going to know. My friends aren’t going to know what to do if I’m being quiet, sitting in the corner alone.”

She’s now taking that conversation from the school hallway to the stage.

For Ella’s mom, the last year has meant more than just relief and pride in her daughter. In a way, the day of Ella’s surgery — Aug. 4, 2021 — felt like a kind of rebirth.

“We call it Life 2.0,” Annie Roehr said.

“A CHANCE OF LIVING A NORMAL LIFE”

Ella still doesn’t know for sure what caused her MALS, but it might be related to her additional diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS), a group of connective-tissue disorders that can cause loose, highly-flexible joints and joint pain.

Whatever the cause, Ella has spent most of her life dealing with health problems caused by her MALS. Those included gastroparesis, in which her stomach muscles had trouble moving; Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which caused an imbalance of her gut bacteria; and Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, which caused dizziness and circulation problems.

Ella experienced roadblocks throughout her treatment when many physicians simply couldn’t figure out what was wrong with her.

“I’d go through the treatments, and nothing would change,” Ella said.

Progress picked up when, about three years ago, Ella began seeing Dr. Bisher Abdullah, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Prime Health Clinic in Puyallup.

Physicians at Prime kept researching her condition as her illness worsened, as well as delivering Ella weekly or semi-monthly infusions over the last year that kept her out of the hospital and let her maintain at least a moderate level of activity.

Heidi Elliott, the registered nurse at Prime who delivers infusions, pointed out that you can’t just tell patients with gastrointestinal issues to eat or drink more water. Their ability to do so is, itself, part of the problem.

“As much as we know in healthcare, there’s a lot more to be discovered,” Elliot said. “We’re still learning a lot about these syndromes.”

If it wasn’t for the support of Ella’s physicians, she would have had to use a feeding tube, Annie Roehr said.

Annie’s own research led her to learn about MALS, which seemed to match many of Ella’s health issues, and she brought that suspicion to Dr. Abdullah. He’d seen MALS before and agreed that it appeared to match her symptoms.

“It’s really essential for the provider to believe the patient, and their family,” Abdullah said. “It’s a balance between what the patient feels is the health issue, and you as a provider with your experience, putting that puzzle together to see if that’s the case.”

It took months more of testing last year with specialists at the University of Washington until, around May, Ella was finally diagnosed with MALS.

“When you have (MALS), the function of these organs decreases,” Abdullah said. “There’s a tremendous amount of pain, nausea, vomiting and weight loss. Any organ, in a human being, when it has less blood supply … it triggers a pain signal. It’s a way to alarm us that there’s a problem.”

Ella flew to Connecticut around August to finally receive open MALS surgery by Dr. Richard Hsu. She spent a month there while preparing for, undergoing and recovering from the four-hour operation.

“They cut me open, in my stomach, all the way back to my spine,” she said. “They took all of my organs out slowly, and they cut out the nerves … a tendon … and they cut and sewed up my diaphragm to release the compression on my celiac artery, so my organs could get enough blood flow.”

Was she scared? “Yes,” Ella laughs. “Very.”

“But I was more looking forward to having a chance of living a normal life and not being in pain everyday,” she added.

Barely able to move, she spent a week recovering at the hospital and another three weeks in a hotel. The flight back home was “no fun” either.

Ella is still in the healing process, which will likely take around a year, and the surgery was no magic “off” button for her conditions.

But four months after the surgery, the gastroparesis is nearly gone. The SIBO is gone. Blood is returning to her nutrient-starved organs, which are finally learning to function at full capacity. Ella still experiences a bit of dizziness, but “that’s not too bad,” she said.

For two years before the surgery, Ella was on a liquid and baby food diet. Now, simply being able to eat food again “is amazing,” she said.

Now performing in her last season on the school cheer team, “I feel like I can breathe,” Ella said. “I can move. I can exercise without having a sharp pain in my stomach.”

“SHE WANTED TO KEEP GOING”

While all this was going on, Ella was busy trying to be a kid.

She’s performed on her school’s cheer and dance teams, as well as taken voice lessons. The pain, dizziness and nausea were constant interruptions that forced her to slow down when she wanted to push herself. But it helped “so much” to have something she had to do — like cheering at a game or going to dance class — rather than sitting alone at home. And Ella had teammates and coaches who understood, sometimes better than herself, when she needed a break.

“Especially at my last dance studio … everyone was so sweet,” Ella said, referring to The Surge Dance Center in Lake Tapps. “The owner was so nice and understanding. … I feel like it really helps for everyone around you to know what’s going on. Even though it was hard to keep going, it helped me so much, especially mentally, to have something happening. … And my cheer coaches are amazing. That helped me too.”

Ashley Naset was Ella’s dance teacher at The Surge last year, prior to her surgery. Naset encouraged Ella to take breaks, get water and cut herself some slack.

“I wanted to make sure she could get what she wanted accomplish, even if it took a little big longer,” Naset said. “There were some times where you could tell she was just beating herself up. She wanted to keep going. … I told her, ‘Go get water. You’re doing fine. You’re going to do better if you get a five minute rest than if you keep going.’”

The word that came to mind for Naset was ‘tenacity.’ Her teachers and peers would have understood if Ella didn’t come to class because of the pain she was in, Naset said.

“But she was like, ‘I need this,’ ” Naset said. ” ‘I need this in my life, this happiness. Even if I’m going to come home and be sicker than I was when I left, it’s going to make me happier in the end.’ I love that she chose it for herself.”

Todd Miller, an agricultural science teacher and FFA advisor at WRHS, taught Ella in his speech and communications class. He recalled the transformation he’s seen from the Ella who started out as a quiet underclassmen.

“When she first started in the speech class, she was very withdrawn, quiet, shy.” Miller said. “As she started to gain confidence and break out of her shell a little bit, she really opened up and got much more comfortable. … She’s a really good kid, she has a strong family backing, and she’s passionate about whatever she does.”

Despite a childhood filled with pain, Ella was always smiling and positive, Annie said, and from their conversations in MALS support groups, Ella has probably helped five or six people get the surgery too.

“I’ve learned a lot from her,” Annie said. “It’s funny how kids teach you.”

But in that happiness is a truth every parent has to face: Your kids grow up.

Annie has spent the last 17 years watching her daughter manage the seemingly never-ending pain. Now Ella’s nearly an adult, and “she doesn’t even seem like the same kid,” Annie said.

And there’s only a little time left before Ella leaves the nest.

“I know she wants to leave for college, and I know we have a lot of catching up and growth to do,” Annie said. “I think the pageant is a great opportunity for her to make up for lost time.”

That’s where Miss Washington comes in.

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION

Her freshman year, Ella met Miss Seattle 2019 Angela Ramous, who is also from Buckley. Miller had invited Ramous (who is now Ella’s pageant coach) to speak about the pageant to his students, and it gave Ella a different look into the pageant world than what she’d seen on TV.

Around this year, she started thinking seriously about doing it herself.

“It was right after I found out I was diagnosed,” Ella said. “I saw a flyer at my dance studio. … I think I watched a pageant TV show, and I thought, oh my gosh, that’s perfect.”

In Miss USA, every competitor has a platform, which is a cause or organization they want to support. Ella wants to raise awareness of her disease so that others who suffer from it “don’t have to suffer as long” as she did.

Ella is not the first teenager to seek help for a condition that mystified many physicians: Connecticut news station News 12 reported in 2019 on Hsu’s first pediatric MALS surgery for a patient who had a similar story.

“There’s been so many things, the social aspect, the connections you make … that were a good reason to join (the pageant) alone,” Ella said. “But my initial drive was making sure it changed the textbooks, that doctors knew about it, that people knew what MALS was. … If a parent knows their infant has these symptoms, if they could get this diagnosed then, and they don’t even have any memories of going through that pain, that’s my dream — for kids to not have to suffer like that.”

She plans to work with the University of Washington to fund research and heighten awareness among physicians of her condition.

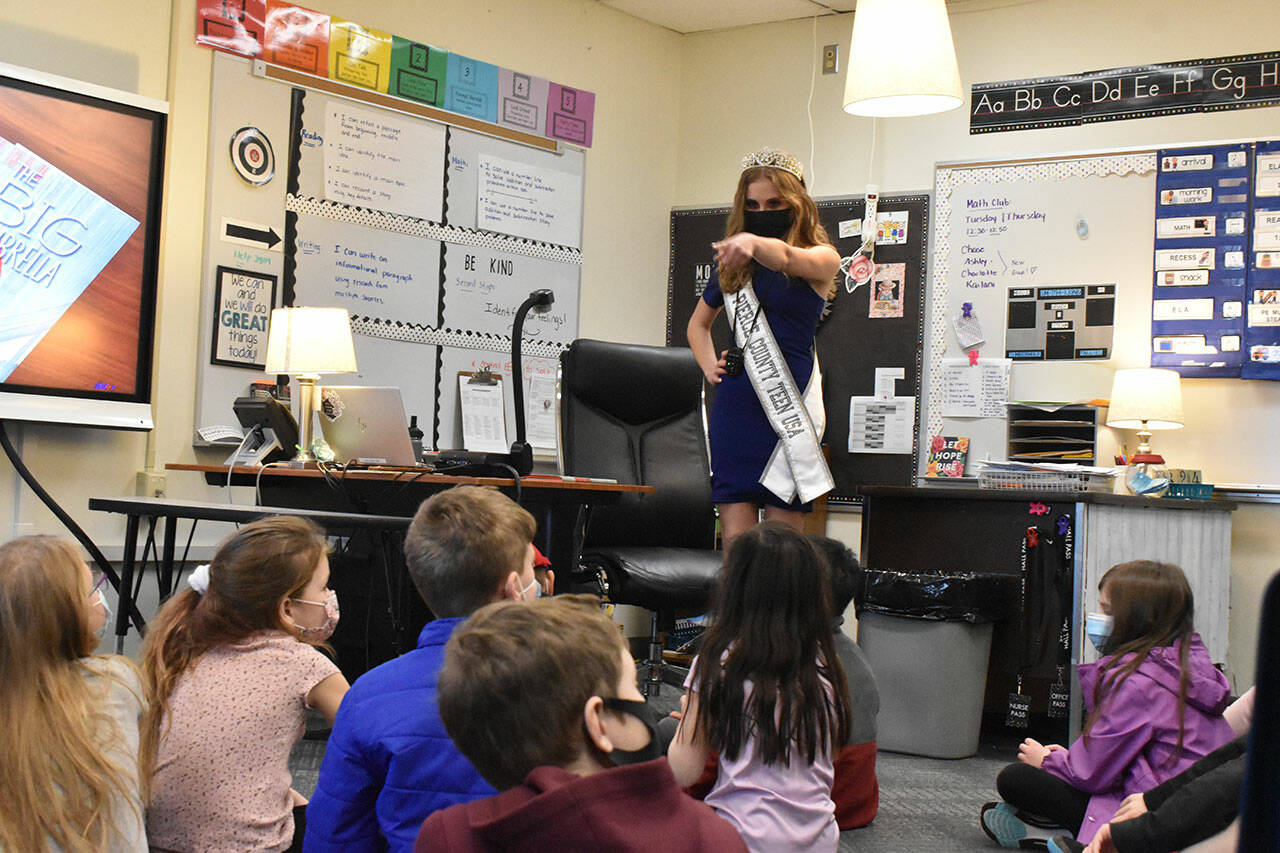

Ella tried out and became Miss Teen Pierce County last spring after a virtual interview process. (Her age category includes ladies from ages 14 to 18.)

This weekend, she will compete in Renton for two days at the state level. Nineteen contestants from around Washington will vie to become Miss Washington Teen, judged in three categories: A 150-second interview with a panel of judges, an fitness wear competition and an evening gown competition. Individual awards will also be awarded in categories like congeniality, spirit, and academic achievement.

Of those 19, ten contestants selected by the judges, plus a people’s choice competitor, will advance first. (Voting for the people’s choice contestant closes an hour before the show starts Feb. 5, online at bit.ly/3Hh8xbo.) That group will then be whittled down by the judges to five contestants for the on-stage questions.

The winner will, naturally, compete this summer to become Miss Teen USA.

Nurse Elliott and Dr. Abdullah from Prime Health Clinic are excited to see Ella compete.

“I’m not her mother, but you feel as proud as a parent,” Elliott said. “I’m proud of Ella’s mother, too. She never put down the boxing gloves. … I think the full circle of suffering is when you can turn around and make it better for somebody else.”

“We all learned from Ella,” Dr. Abdullah said. “We learned to be better listeners, more patient, meticulous.”

The limelight can be intimidating, so how does Ella hype herself up?

“It sounds kind of silly, but I sit in my car and crank up rap,” Ella said with a laugh. (Her go-to is rapper/songwriter Cardi B.)

Maureen Francisco, the executive producer of Pageants Northwest, organizes the show and interviews the ladies who go on to compete.

Contestants will sometimes look for excuses like their height or ethnicity when they don’t feel confident in their performances, Francisco said, and she found it commendable that Ella didn’t see her health conditions that way.

“With Ella, it wasn’t about that,” Francisco said. “It was: ‘I can do anything I set my mind to despite having health challenges.’ That really drew me, because I’m looking for confident women, or women … (for whom) we can instill confidence in them.”

In addition to instilling confidence and shattering stereotypes for the girls and women who compete, Francisco said one lesson from the pageants is that the hard times will pass — and that “the best years are ahead of them.”

After a decade-and-a-half of pain and struggle, Ella might know that better than anyone. She’s going through the college application process now, “but more than anything, I want to travel and see the world,” she said.

“(Travel) is something I’ve always wanted to do with my life, but I had never thought it was realistic,” Ella said. “I always needed to stay kind of close to my doctor, or make sure to bring a bag of pills into the airport. … If I win, I really hope I get travel opportunities to talk to people about it. I’d be able to go see people and places that aren’t in my network, or don’t see me on social media.”