Corrections: Additional information was provided to the Courier-Herald after print deadline, and the online article has been updated. Updates include why Stevan Knapp lost his parole and was re-sentenced in 1990, when he was admitted to McNeil Island’s total confinement facility (1999 or 2000, not 1998), and when he was admitted to an LRA on McNeil Island (2018). Additionally, the Courier-Herald mistakenly referred to RCW 26.60 instead of King County Code 21A.06.450 in regard to zoning code. Finally, some math was incorrect in regard to monthly payments to Garden House, and has been corrected.

Hundreds of Enumclaw residents are banding together in an attempt to stop high-level sex offenders from moving into a community home outside the city.

What started as a group of a few dozens worried neighbors along SR 164, just south of the White River Ampitheatre, has turned into a Facebook page with nearly 700 members looking to learn about the process of moving sex offenders off McNeil island and — maybe most importantly — how to stop offenders from being moved locally.

Here’s the situation: a home off 188th Avenue SE recently signed a contract with the Washington State Department of Social and Human Services last August to house Level 3 sex offenders being released from McNeil Island’s confinement facility (located east of Steilacoom), where offenders are civilly committed after they complete their prison sentence.

Garden House is run by Jill Rockwell, who has a Burien PO box. Rockwell is married to Rick Minnich, who runs Minnich Polygraph Services and provides services to the DSHS when violent sex offenders are being considered for relocation off McNeil Island.

The Courier-Herald has attempted to contact Rockwell and Minnich, but did not receive a response by print deadline.

Garden House is what’s called a Less Restrictive Alternative, as opposed to a secure facility run by DSHS.

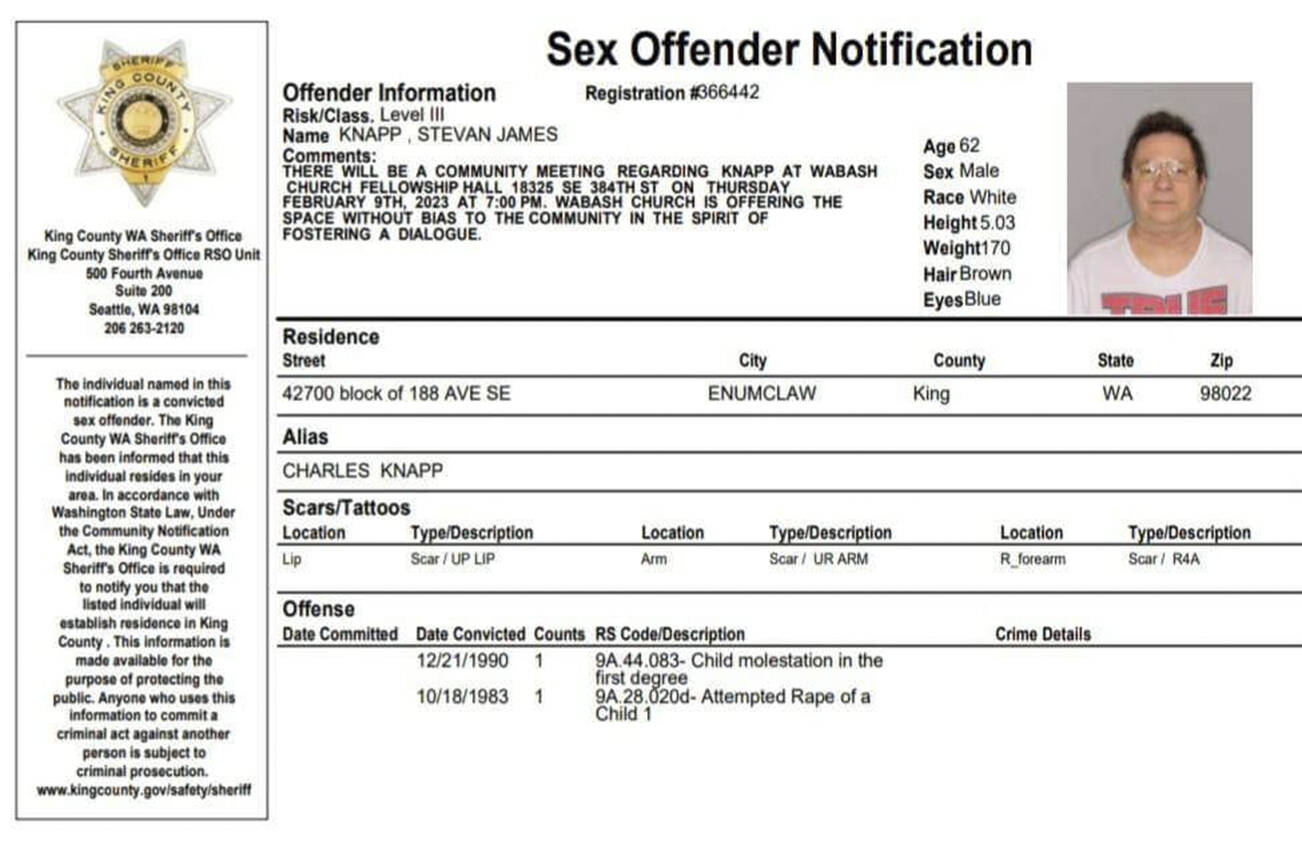

Its sole resident at this time is Stevan James Knapp, who was convicted of sexually-violent crimes against young children and sent to the Washington Corrections Center in 1986. Knapp was paroled in 1989, but it was revoked after he committed another violent sexual offense, and he was given a new sentence in 1990.

Knapp was released into civil commitment on McNeil Island in 1999 or 2000 (sources differ on the year), and was placed into an LRA on the island in 2018. That same year, he was removed from the LRA and placed back into the McNeil total confinement facility, but he was placed back into the same LRA in 2019, where he lived until he was relocated into Garden House mid-January 2023. Other offenders are expected to move into the LRA in the future.

In response to his relocation to Enumclaw, roughly 36 concerned residents gathered together on Jan. 24 to express their worries, ask questions and provide answers, and discuss strategy for how they could possibly force the LRA to close or move.

Many were upset that it appeared the state was trying to do this “quietly and quickly”, without giving locals the chance to voice their opposition; others wondered what sort of security features Garden House had on its premises, and what sort of police response is possible if Knapp or other residents tried to escape; and still a few more questioned how Rockwell and Minnich were able to secure this contract and how much money they may make.

Since then, a “Save our Children — Enumclaw” private Facebook page has been created with more than 1,100 members, though some are not local and are concerned with a similar situation in Tenino.

A community meeting is being held Feb. 9 at Wabash Church (18325 SE 384th St, Auburn), starting at 7 p.m., by DSHS, the Department of Corrections, and the King County Sheriff’s Office, to address the situation. A follow-up report about the meeting will be in the next edition of the Courier-Herald. Expected to be in attendance will be city council members, King County officials (or their staff), and legislative representatives.

However, DSHS’s Behavioral Health Administration media relations spokesman Tyler Hemstreet provided some general answers to how the LRA process goes.

In short, he said, what’s happening in Enumclaw is more-or-less business as usual; the state has been moving McNeil offenders to LRAs for at least a decade, though Hemstreet said DSHS doesn’t “have exact data” on when this process began.

Hemstreet’s said this process of moving offenders from McNeil Island to LRAs is inscribed in Washington state law, and is not done at the discretion of Gov. Jay Inslee or the DSHS.

“These discharge options are not controlled by DSHS. This is all controlled by the court — the court approves this, the court approves that,” he said. “All we’re doing is following the law, and the providers are following the law as well.”

Under RCW 71.09, after a high-level sex offender (Level 3 is the highest, and indicates a high risk to re-offend) finishes their prison sentence, a prosecuting attorney can petition to have the offender move to McNeil Island for civil commitment — another phrase for involuntary commitment — and long-term treatment.

All residents of McNeil Island are required to undergo an annual review to determine if they are far enough along in their treatment to be moved to an LRA. The report also includes what sort of conditions should be in place to protect nearby communities.

According to Hemstreet, the annual review is performed by a Forensic Services Unit, a team of eight psychologists.

If they recommend the offender be moved to an LRA, the review is checked over by a separate team of medical professionals and licensed psychologists called the Senior Clinical Team

Finally, if the Forensic Services Unit and the Senior Clinical Team agree on their recommendations, their findings are sent to McNeil Island’s Chief Executive Officer for approval.

Once the CEO gives the green light, the annual review is considered by a judge, who has the final say on whether the offender will be relocated.

With the conditional LRA release approved, the offender then completes sex offender registration, meets with the Department of Corrections, and moves into the facility or home.

COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWN

When an offender is scheduled to leave McNeil Island, DSHS sends a notice to a county sheriff’s department 30 days prior to the scheduled release.

The sheriff’s department, in turn, may inform local communities about the placement of the offender; according to Hemstreet, there is no Washington state law requiring sheriff’s departments to do so.

In King County, residents have to sign up to receive sex offender registry alerts though the Sheriff’s Office website.

However, it appears there was a breakdown in communication between DSHS and KCSO.

According to King County Sheriff’s Department PIO Sergeant Mark Ford, the department was made aware of Mr. Knapp’s release from McNeil island in a timely manner.

“However, we were not notified that this particular location would be used to house [Registered Sex Offenders],” Ford said in an email interview, adding they were notified of the LRA at a later time. “We are currently working with DSHS and DOC to improve communication and notifications.”

Currently, there is no state law requiring DSHS to inform either sheriff’s departments or the public at large that an LRA is being operated in the area.

That could change — House Bill 1734, co-sponsored by local Rep. Eric Robertson (R-31), was recently submitted to the state legislature, and if passed, would require the DSHS enter into a contract with an LRA provider after a public notification and comment period and other ways local government and communities are notified and can communicate with the state regarding the LRAs and their residents.

Ford added that KCSO doesn’t notify the public that a registered sex offender is moving into an area until the RSO officially registers themselves into the sex offender registry at the King County Courthouse, rather than when DSHS gives their notice of the scheduled release.

WHY MY NEIGHBORHOOD?

According to Hemstreet, Washington state operates under “Fair Share” rules — created by Senate Bill 5163 in 2021 — which requires counties to supply adequate LRA housing for the number of violent sexual predators convicted in their jurisdictions.

With King County having the highest population, it stands that it also has the largest number of violent sex offenders, and thus needs the most housing; the county has four LRAs contracted with DSHS, and a fifth not contracted with the agency. These LRAs are currently housing 12 residents, and a 13th is living with a family.

“You’re not going to get a lot of humanity for the residents, in what they’ve done. But they’ve served their time in corrections and they have to get an opportunity for their civil commitment to end,” Hemstreet said. “Ultimately, their goal is to progress in their treatment and get off the island to a Less Restrictive Alternative, which could be community housing, and then eventually to non-restrictive, so they don’t have an ankle bracelet.”

Some people who find themselves living near LRAs become determined to find a way to force the homes to close or move locations, and Enumclaw is no exception.

In 2019, Kitsap County attempted to close an LRA outside Poulsbo after resident outcry. Initially, a Hearing Examiner declared the home to have violated zoning codes, but a judge that December reversed the decision, and the home continues to operate. It’s unclear if this this issue has progressed since.

“Unless you change [RCW] 71.09, you can’t stop it,” Hemstreet said. “Nobody wants folks there, but the law is very clear that we have to have options.”

A LOOK AT THE CONTRACT — PAY, ZONING, REGISTRATION

Rockwell’s contract with DSHS was signed Aug. 30, 2022, and lasts through June 30, 2024.

According to the contract, Garden House’s rate schedule includes a fixed rent rate of $5,600, but an adjusting rate for utility fees, administrative fees, and special additional pay based on the number of residents living at Garden House. For one resident, DSHS will pay the LRA $7,400 a month; at max capacity, with six residents, total monthly payments come out to $11,900 a month.

Over the 22 month contract period, a full LRA would bring in about $262,000; the contract maximum is $285,600.

The contract appears to only allow up to six residents to reside at the LRA.

The contract also stipulates that prior to accepting residents, Garden House must be zoned properly. The parcel is currently zoned as A-35, or an agricultural zone that limits one dwelling unit per 35 acres; according to King County Code 21A.06.450, “a group of eight or fewer residents, who are not related by blood, marriage or state registered domestic partnership” can live together in a home zoned A-35.

Finally, Rockwell is solely responsible for operating Garden House, which includes everything from administrative services and bookkeeping to installing all protection and security equipment.

At this time, it does not appear that Garden House is registered with the Secretary of State as an limited liability corporation, a nonprofit, or other entity, though the contract with DSHS has a Unified Business Identifier (UBI) and is registered with the Washington State Department of Revenue.

FURTHER QUESTIONS

There remain many questions regarding Garden House.

At this point, the Courier-Herald has requested numerous documents and records, including Knapp’s annual review and set conditions for his residence at the LRA; communications establishing a chain of contact alerting appropriate parties of Knapp’s move to the LRA; data regarding how many LRA residents offend during and after living in the home; and records of DOC’s security review of Garden House.