By Brenda Sexton-The Courier-Herald

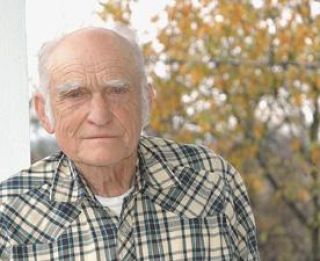

Every morning Enumclaw Thoroughbred owner, breeder and trainer Don Munger rises, he celebrates. He finds joy in the trill of a songbird, sunrise on The Mountain that provides a backdrop for his Plateau farm and a homecooked meal with his wife Wanda.

“You just appreciate being alive and being here,” the World War II veteran said. “That war left its impression on you, but it taught me things, too. It taught me to value life. You value life more while you're about ready to lose it.”

Munger understands the 18-year-olds, like himself once, who were, or are fighting, for the life he has now.

He was an anxious teenager a day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. It was Dec. 8, 1941, when Munger jumped in line at the Marine recruiting office (it was shorter than the Navy line, he laughs) and tried to enlist. They made him wait - three days - until his 18th birthday.

“We wanted to go,” he said. “It's completely different now.”

It wasn't long before Munger found himself as a scout sniper, one of the first for the Marines, in the Pacific Theater. By February 1945, Munger was slogging the rough volcanic ash of Iwo Jima.

The Marines would lose nearly 7,000 men and bring home another 20,000 wounded in an effort to control the island and its vital airfields. The Japanese dead in defending it would total 18,000.

Munger was a member of the 3rd Marine Division, a reserve squad that didn't storm the beach in the initial attack. But when casualties started piling up, he was called into action.

“They sent us in for reinforcement. The place was littered with bodies,” Munger recalled. “There was so much confusion, people were getting killed so fast.”

The Japanese hunkered down in an intricate tunnel system that covered the tiny island and were heavily armed.

“You couldn't see the Japanese. You were constantly under fire,” he said. “You were always in range of the cannons and mortars.

“It was really a hot spot.”

Amid the chaos, a handful of Marines illuminated history and inspired a nation as they charged to the island's highest point and raised the American flag atop Mount Suribachi during the battle. A photograph taken of the event became instantly famous.

“It stood up like a sore thumb, like Mount Rainier here,” Munger said of Mount Suribachi. “We all seen that flag up there. That was a real morale booster.”

Old Glory, no matter where she billows, can still turn an Old Salt into a softy.

“Every day at the flag raising at the track (Emerald Downs) and they sing the Star Spangled Banner, many times I have a hard time keeping the tears back,” Munger said.

When movies like “Flags of Our Fathers,” based the 2001 James Bradley novel of the same name, about the rising of the flag over Iwo Jima hit the media mainstream, Munger said they conjure up memories about his days there.

“I fight this war every night,” Munger said. “I have good memories of my buddies. I think about them daily, but I fight this war every night.”

“There's no way you can explain what it was like,” he said. “It wasn't always as easy to talk about. That's why some Veterans don't want to talk about it. There's no way you can explain it - what it was actually like, like the concussion, the ground shaking from the shells, the smell of the gun fire, bullets whizzing by.”

“I've been lucky so many times,” he said. “I offered mine (life) and like I said I lucked out. The Lord was watching over me.”

Munger's life was nearly lost a half dozen or more times just on Iwo Jima. He can outline each and every one of them with pinpoint accuracy.

There was the time he jumped in a shell hole to protect himself from a barrage of mortar fire. Two others joined him in the tiny dugout - too many he thought, so he bailed out to find another hole for protection. He was not far away, desperately trying to scoop out a foxhole for protection with his dinner plate, when a mortar hit the hole he had recently abandoned, killing the soldiers inside.

Another night he camped with a comrade on a narrow ledge with just enough room to duck behind the constant fire. Munger escaped the attack, but his fellow Marine was not as lucky.

“You were never out of range, so you could never relax,” Munger said. “I was extremely lucky.”

And then there was close call that dinged him up and sent him home.

After parading a “mentally” wounded mate back to the dispensary, Munger decided the shortest way back to his platoon was across one of the coveted asphalt airstrip that happened to be occupied at one end by Japanese forces and at the other by American troops.

“I decided to split the airfield,” Munger said. And he was doing OK, until a group of U.S. tanks came up alongside of him and the Japanese opened fire.

“I couldn't dig in and I couldn't dig a fox hole,” he said. So he just hunkered down and waited, the force of each strike bouncing him along the airstrip.

To make it worse, once he eventually cleared the airstrip, he had to weave his way in and out of a series of ravines making him target practice for Japanese sharp shooters. Once again, he said, he was doing well until the tanks decided to park in front of the ravines.

Injured enough to slow him down, Munger was sent home - four years after enlisting.

But the war has never left him.

“Don still has his sea bag packed,” Wanda Munger smiles.

He also keeps a bottle of sand from the Iwo Jima beaches he picked up not while he was there - there was no time for that - but at a Marine reunion. And through the years he has named some of his horses after military terms like Parapet, Old Salt and Screamin' Gertie (named for the Japanese weapon that bombarded Munger).

Munger said he still fights the war nightly, but he also wakes up every morning and says, “It's sure great to be alive.”

Brenda Sexton can be reached at bsexton@courierherald.com.