Mount Rainier has always been popular — but increases in visitors, according to officials, is affecting how hikers experience one of the nation’s favorite national parks.

According to the National Park Service, the number of recreational visitors has risen more than 600,000 between 2008 to 2021, from 1.1 million to above 1.7 million.

That’s not necessarily an issue in itself — but the fact that 70% of visitors only come between July and September, and that most of the areas being visited are just a small number of destinations like Paradise and Sunrise, is causing the park’s most attractive areas to be crowded.

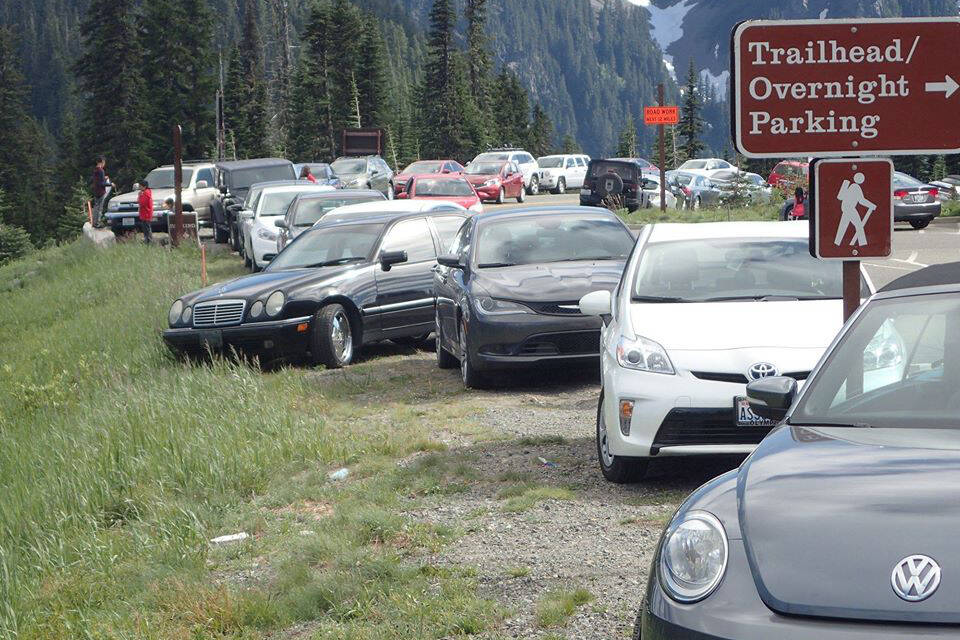

“Visitors currently experience wait times of more than an hour to enter the park through the Nisqually and White River Entrance Stations on busy days, causing congestion both inside and outside of the park,” Chief of Interpretation, Education and Volunteers Terry Wildly wrote in a recent press release. “Roadway congestion also occurs within the park at popular trailheads, which leads to parking in undesignated areas and pedestrian safety concerns due to limited roadway visibility.”

The increase in traffic — both vehicle and foot — is also having an impact on local flora.

“Many of the people who are drawn to Mount Rainier National Park come to see the spectacular wildflower blooms each summer. As visitation has grown, we have seen impacts to the subalpine meadows where the peak wildflower blooms occur associated with increased travel off-trail, including the areas adjacent to the trails as people step aside to allow other groups to pass,” said Park Planning & Compliance Lead Teri Tucker in a recent email interview. “The actions proposed in the draft plan are intended to both help ensure a less crowded trail experience at Mount Rainier while also protecting the meadows and wildflowers that many people hope to see and experience during their visit.”

To reduce congestion and protect the park’s natural state, National Park Service is proposing three plans to manage the pace and entry of vehicles into the area. A reader-friendly Story Map of the draft plan, which includes how the park would be affected, can be read at tiny.cc/vpm6vz.

One option, which the National Park Service prefers, is installing a time-entry reservation system during peak times at the Nisqually and Stevens Canyon entrance stations. This would limit the number of people that can access portions of the park that can be accessed on Paradise Road East and Stevens Canyon Road during the peak season (July through Labor Day) at peak times (7 a.m. to 5 p.m.)

According to the draft plan, this reservation system would put cap the number of cars (800) and people (2,400) that could access note just Paradise, but the Cougar Rock Campground, Snow Lake, Pinnacle Peak, and more.

A second option is to install a reservation/shuttle system only at Paradise parking lots.

This option also comes with adding a shuttle service that would take those who parked at Cougar Rock without a reservation to Paradise; primary access would still be via private vehicle, as shuttle usage would be “first come, first serve”.

This option would cap the numbers of cars at Paradise lots to 730 and about 2,500 people.

A final option (not counting “do nothing”) is to do away with the Cougar Rock shuttle and only install a parking reservation system at Paradise.

This would bring down the visitor cap to about 2,200 people in the Paradise area.

All options would limit parking on Paradise Valley Road in some fashion, which “during the summer months, there are more cars parked on Paradise Valley Road than in any designated parking lot”, the draft plan reads.

All options would also come with installing a reservation system at the White River entrance of the park, which would out a cap on cars and people at Sunrise.

Though a reservation system may work at reducing congestion, it may also negatively affect the park.

There could be short-term impacts as long- and first-time visitors may be caught unaware of a new reservation system and get turned away at the gate.

“Although these impacts may occur during initial implementation of the system, the long-term beneficial impacts of reduced crowding and congestion would be expected to outweigh the adverse impacts of adjusting to a new system,” the draft plan reads.

However, “The climate of the Pacific Northwest often causes cloudy and overcast days when Mount Rainier is not visible. The park sees an uptick in visitation during sunny and blue-sky days when the ‘mountain is out’ and visible to Washington State residents. A reservation system prevents spontaneous visitation and, therefore, would adversely impact this type of desired visitor experience,” it continues. “Furthermore, this action may have indirect effects as visitors who are unable to obtain a reservation are displaced to other areas of the park or surrounding public lands. In contrast, those who use the reservation system would be expected to have a higher-quality visit in the context of predictability of access and reduced crowding and competition for parking within the corridor.”

The public comment period on these three proposed plans opened April 26, and closes June 11.

To read the full draft plan and submit comments, head to parkplanning.nps.gov/NisquallyCorridorPlanEA.