Two bills that aimed to change how sexually violent predators are placed in Washington state communities, and a third attempting to pause that placement altogether, were introduced during the 2023 legislative session.

But all three bills — Senate Bill 5739 and House Bills 1734 and 1813 — failed to make it out of their respective committees by the Feb. 17 deadline, making it highly unlikely they’ll be debated on the floor of the state House or Senate this session.

Their local sponsors, Sen. Phil Fortunato and Rep. Eric Robertson (R-31), have said this setback won’t keep them from continuing to fight for transparency and accountability in a system that has angered Enumclaw community members — due to what those community members see as an unconscionable lack of communication and consideration from the government and a failure to keep the community safe.

The spotlight of national news attention reached Enumclaw earlier this year when Stevan Knapp, a convicted level three sex offender, moved into a group home for offenders called Garden House without any communication from the state or opportunity for public input.

“There is an old saying: ‘No bill is really dead until the last gavel falls’,” said Robertson in an email interview. “With the failure of the chairman to hear the legislation, I will admit that HB 1734 has a bleak future during this session; but I will continue to advocate for policy which creates transparency and community notice when sexually violent predators are place[d] in any community setting.”

Here’s a summary of the bills, which tackle their own issues regarding government communication when it comes to placing Less Restrictive Alternative hosing in communities, when violent sex predators are relocated into those LRAs.

A Less Restrictive Alternative (LRA) is a general term for a home for one or more high-level sex offenders that are being released from the DSHS-run McNeil Island Special Commitment Center; its name refers to the fact that these homes are not state-run and do not require complete confinement of its residents.

Note that even though Enumclaw and other affected communities have expressed anger over the release of offenders from McNeil Island, let alone their release into Enumclaw, these three bills would not permanently prevent the release of sexually violent predators from McNeil Island or require offenders be permanently civilly committed to a treatment center.

“There [are] constitutional issues here,” Fortunato said in a recent interview, noting these offenders being released from McNeil Island have served their prison terms and can’t be held in civil commitment on the island indefinitely if they’re found to have progressed in treatment far enough to be placed in an LRA.

HOUSE BILL 1734 — NOTICE OF LRA PLACEMENT

Under current state law, the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) is not required to inform communities that a Less Restrictive Alternative home is opening in their area.

HB 1734 would have changed that, and add other requirements to how DSHS goes about establishing LRAs to current Revised Code of Washington 71.09.097.

According to the original code, DSHS is required to follow the request for proposals process to solicit and contract with housing and treatment providers in order to establish an LRA. This means, in short, bidders would submit a proposal for how much their services would cost, and the government would choose the contract that has the “best value procurement” which means selecting the proposal that best meets the government’s goals. This can mean, but is not always determined by, the lowest cost.

Request for proposals are also public, and are often advertised in newspapers and other publications.

However, according to DSHS spokesman Tyler Hemstreet, DSHS enters into what are known as “services contracts” with LRAs, and these are exempt from the RFP requirement under RCW 71.09.097.

It should be noted that the vast majority of LRAs across the state also do not contract with DSHS, but enter into contracts with the court system, which does not require a request for proposal.

As for the exception of Garden House, which is contracted with DSHS, Hemstreet said that though it was not required, the department did issue a request for proposals as a way to cover all bases, but the RFP went unanswered.

It’s unclear if this was the first RFP the department has issued for a contracted LRA, or if DSHS has issued past RFPs for the few other LRAs it has contracted with.

HB 1734 would not amend 71.09.097 in order to require service contracts undergo the RFP process.

However, it would add a new section requiring that DSHS must issue public notice and establish opportunities for public comment before entering into a contract with a proposed LRA.

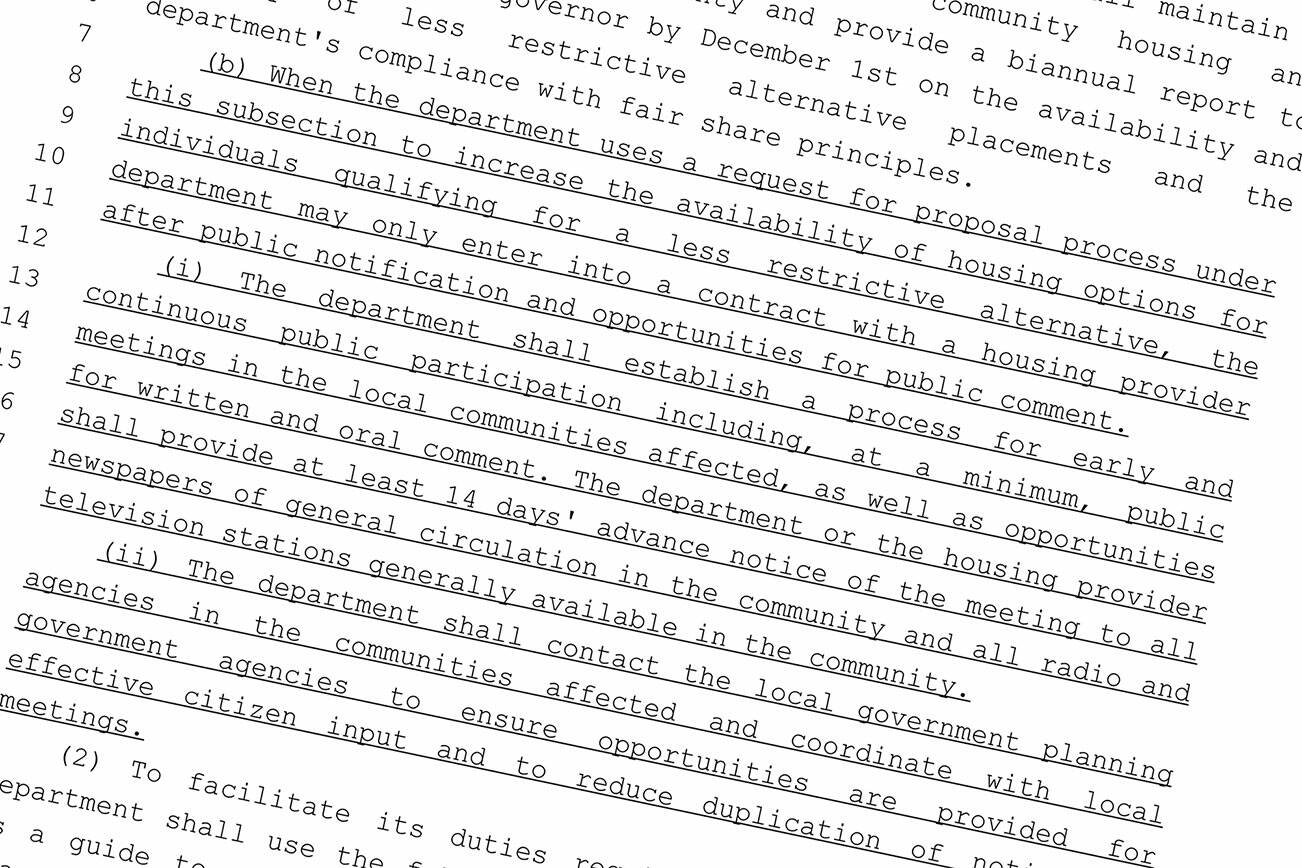

“The department shall establish a process for early and continuous public participation including, at a minimum, public meetings in the local communities affected, as well as opportunities for written and oral comment,” the bill reads. “The department or the housing provider shall provide at least 14 days’ advance notice of the meeting to all newspapers of general circulation in the community and all radio and television stations generally available in the community.”

The bill would have also require DSHS to contact local governments and other agencies in affected communities to increase the chances of citizen input.

However, since most LRAs are contracted with the courts and not DSHS, it’s unclear if this amendment to the RCW would have provided the public with much additional notice.

This bill was submitted to the Committee on Community Safety, Justice, & Reentry, chaired by Rep. Roger Goodman (D-45).

According to Goodman, the bill was introduced too late in the session to hold a hearing or vote and will have to wait until next session, citing that the overall issue with sex offender releases into LRAs is complex and will require working closely with many stakeholders, including at least concerned residents, the DSHS, and attorneys of those being held on McNeil Island.

SENATE BILL 5739 — COMMUNITY NOTICE OF SVP RESIDENCE

Under current statute, all community notice of when a sexually-violent predator moves into their area is provided by the relevant counties, though it is not a requirement under state law.

In King County, the Sheriff’s Office sends out notices to those who sign up for them via sheriffalerts.com when a sex offender registers with the county. However, that registration is typically done after an offender has begun living at their new residence.

SB 5739 would have changed this in a major way, requiring DSHS, not counties, to provide notice that a violent sexual predator would be moving into their community at least 30 days before an offender’s scheduled release from McNeil Island.

Local legislators would also be notified, as Fortunato made it clear in an interview he was upset that he found out about Enumclaw’s particular issue with its LRA, Garden House, and resident Stevan Knapp, from constituents, as opposed to DSHS.

The bill would also require the notices sent to community members would include the address of the sex offender’s residence.

Finally, the bill would increase the distance a sex offender out on conditional release could live from licensed child care centers and schools from 500 feet to two miles.

Garden House is approximately 1.7 miles away from an Enumclaw School District elementary.

The bill was referred to the Committee on Human Services, chaired by Sen. Claire Wilson (D-30).

Wilson and her office did not respond to a request for comment by print deadline.

HOUSE BILL 1813 — MORATORIUM

House Bill 1813, sponsored by Robertson and several other representatives, would have temporarily paused the release of sexually violent predators from the McNeil Island treatment center into LRAs, and would have also required DSHS and the courts from entering into contracts with LRAs.

The bill also would have created a legislative work group on siting future LRAs, which would consist of one member from both parties in the Senate from the Law and Justice Committee and the Human Services Committee, plus one member from both parties in the House from the Community Safety, Justice, and Reentry Committee, the Civil Rights and Judiciary Committee, and the Local Government Committee.

Joining them would be six members representing two survivors of violent sex crimes, the Office of Crime Victims Advocacy, the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, a licensed sex offender treatment provider, and the Washington State Association of Counties, the Department of Social and Health Services, the Department of Corrections, and the Sex Offender Policy Board.

The group would work on siting criteria for future LRAS, including looking at providing opportunities for local control by cities and counties.

The group would also look at suggesting amendments to RCW 71.09, which, in part, is the code that controls how offenders are released off McNeil Island into LRAs.

However, a moratorium on releasing sex offenders from McNeil Island — as noted by Fortunato — could be construed as unconstitutional, as it could be argued that delays in releasing offenders that are deemed ready to leave McNeil Island would violate their civil rights.

The bill was referred to the Committee on Community Safety, Justice, and Reentry, chaired by Goodman.