CORRECTION: This article has been updated with additional information provided after print deadline; A quote was taken out of context in the print version of this article. Mother Rosa Arnold, in a quick phone conversation, said, “My son is going to die if nothing changes” in regard to alleged death threats, not due to a lack of available support or treatment; Additional quotes have also been added from Rosa and father Jonathan; legal standards regarding the Invountary Treatment Act have been clarified; and Jonathan Jovaughn Arnold was not arrested after a May 1, 2021 incident, but was already in custody when charged with harassment and sexual assault.

“Caged.”

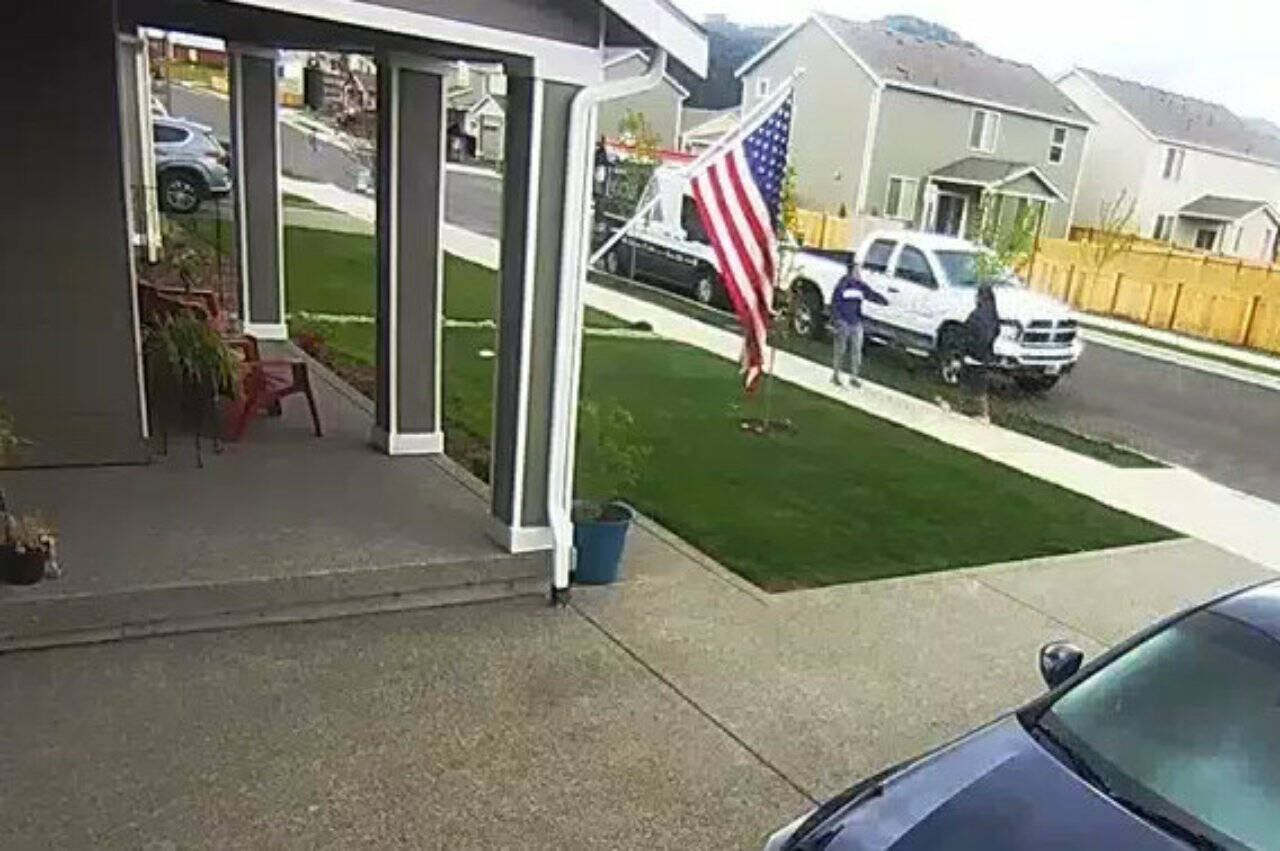

That’s how one woman describes her life in an often-quiet Suntop Farms neighborhood — when things are great, they’re great, but when her neighbor is back in town, the whole street tenses up, waiting for something to happen.

Jonathan Jovaughn Arnold, 30, has been accused of multiple incidents of sexual harassment and fourth degree assault with sexual intent since at least 2018, according to Washington State Patrol, Enumclaw Police Department, Seattle Police Department, and Snohomish District Court records, plus a state Department of Social and Health Services mental health report.

However, many — if not most — of these incidents have never been met with consequences because Arnold, who suffers from a traumatic brain injury, is consistently found to be unable to stand trial.

Due to his condition, the Courier-Herald did not reach out to Arnold for comment, but his parents instead; his mother responded to questions via email.

Locally, Arnold has been arrested at least six times, all on misdemeanors.

The EPD began receiving calls about Arnold in January 2021, shortly after he moved into the area, but the incidents were small; police reports note alleged “unwanted subject,” “trespass” and “disturbance.”

That changed on May 1, 2021, when Arnold sexually harassed and assaulted three women on his street. Because of the nature of these crimes, the Courier-Herald will not publish the names of the victims nor the specific street on which this occurred.

According to the EPD report, Arnold approached the first woman and was sexually vulgar.

After being told to leave, Arnold then found the second woman, who was carrying her grocery bags into her garage from her car. According to the EPD report, Arnold “ran into her garage” at the woman before leaving.

Finally, he approached the third woman, who was going to her mailbox, and began to follow her, pretending to be on his phone but continuing to be sexually inappropriate.

This time, when he was told to leave, he closed the distance between him and the woman, who backed up, arm out between her and Arnold, to her front door. According to the EPD report, he got into arm’s length of the woman and started “fumbling with his … hand down his shorts.”

Arnold, who during the ensuing investigation was in custody after a different incident, was then charged with sexual harassment and fourth degree assault with sexual intent.

City Prosecutor Krista Swain secured a conviction, the only time in Enumclaw that he received a sentence. As part of his sentence, he was ordered to undergo mental health treatment.

However, in a later case stemming from a protection order violation, he was found unable to stand trial, and the judge’s earlier ruling for continuing mental health treatment was effectively vacated.

His next four arrests were for alleged protection order violations — by May 8, 2021, six women on Arnold’s street already had protection orders against him.

Other alleged incidents of alleged sexual assault include: assaulting a Burien nurse in October 2021, followed by an EPD arrest for a protection order violation and exposing himself to female correction officers while in jail; approaching several women and touching himself at Columbia Tower in Seattle last March; and exposing himself on his street after a woman walked by last June.

According to Prosecutor Swain, the court received yet another competency evaluation showing he is unable to stand trial for the latest charges, and the case is slated to be dismissed.

All in all, neighbors called police more than 25 times over two and a half years in regard to Arnold, though one person said some incidents were simply not reported. While most calls did not result in an arrest, these incidents and others have had a severe negative impact on the community. Some of Arnold’s neighbors said that one family even moved out of Suntop because they did not feel safe; at least one other has considered it, but is also concerned about uprooting his family after they’ve become established in their new community.

“Those of us who are on this block are, unfortunately, super… vigilant,” one neighbor said, noting that when Arnold is in custody, it’s like the street takes a sigh of relief. “But as soon as I see him sit on that front porch, I know that we’re all back on guard.”

“I have to keep my head on a swivel, because he either sneaks up or tries to attack or is just masturbating in front of you,” another resident said. “I have PTSD from the time that he attacked me. I’m constantly living with anxiety.”

“I lived in Renton, at The Landing, for ten years where the public transportation was below the building, and I never had one incident,” a third resident said. “I was really shook when I moved here.”

Alleged victims have said that Arnold’s family members have retaliated against them via their own protection orders, threats of lawsuits, and an investigation by the Department of Social and Health Services’ Adult Protective Services department.

The DSHS confirmed the investigation was closed as “inconclusive.”

UPENDED LIVES AND A VICTIM OF THE SYSTEM

In several email exchanges, mother Rosa Arnold talked about how her son had a head-on collision with another player during a rugby match, resulting in a skull fracture, sinus cavity fracture, and broken nose; medical records show he had surgery to replace part of his skull with a metal plate and put eight screws his forehead.

“He got back on his feet as soon as possible, after a grueling surgery that he survived,” Rosa continued. “He’s always been a fighter, so he recovered quicker than expected, although it wasn’t advised that he got back to school as soon as he did.”

According to her, Arnold wrote about his trauma for his University of Washington college admission essay and was able to finish a “challenging” senior year. However, it was a year after that when “he started to encounter difficulties,” and his family started looking at various support and treatment options.

“Trying to find treatment is almost nonexistent and we’ve done everything known to man and in the realm of our power. Which has been like pulling teeth since we, as parents, and even legal guardians at one point, have little to no rights or say in the matter,” Rosa said. “We have met roadblock after roadblock and we have found the only good the legal guardianship or being a parent have gotten us is someone to point the finger at and blame.”

One of the biggest issues to treatment is cost.

“Even with three insurances, we’re not able to accomplish much,” she continued. “Once I carried Primera insurance with my company in addition to my husband’s. I couldn’t wait to report it to our son’s outpatient, only to be told they didn’t accept our private insurance, nor did any other state outpatient care, they only accept our son’s state insurance. Therefore, what good is insurance that we pay expensive premiums for, when we cannot get them to provide the help we need for our son.”

All the Arnolds thought they could do, then, was move somewhere that could be better for their son.

“We left everything behind and relocated here to help him medically and morally, and have done everything we know how to get him the help he needs and advocate for him,” she continued, noting that Arnold’s caregivers, legal counsel, and “other locals” encouraged them to move away from more populated residential areas, “where we had no desire to live, nor knew absolutely anything about.”

But given the “backlash/harassment” they’ve experienced in Suntop — a “cease and desist” letter reportedly sent by father Jonathan Arnold to neighbors alleges “rallying,” “yelling,” “inciting violence” and “sharing personal identifiable information… on social media,” actions those neighbors have denied — “we are currently attempting to get job transfers to another state or different location here,” Rosa concluded. “We love him and have mourned the loss of who he used to be. He has lost himself and we can’t discard him like trash when he most needs us. God allowed him to survive this horrible accident for a reason.”

Rosa said that her family doesn’t condone her son’s actions, but noted that he has not been arrested for or charged with any felony, and that he is also a target of harassment and physical violence.

At this time, Arnold reportedly receives outpatient treatment with Seattle-based Community House Mental Health Agency, which offers myriad services including shared supportive housing and 24-hour staffed licensed assisted living facilities. The agency did not respond to a request for an interview regarding treatment barriers by print deadline.

THE INVOLUNTARY TREATMENT ACT: WHAT’S A “SERIOUS” THREAT?

Every neighbor contacted said they want Arnold to get the treatment he needs to be healthy — but, some neighbors said, that would require 24/7 supervision, likely in a care facility and not at home.

“We don’t want to keep calling the cops and send him to jail,” one person said. “He’s a danger to the people that live here and he can’t get help.”

But given the barriers the Arnolds have reportedly encountered (no documentation was provided along with claims), his neighbors are left wondering, then, why the county or state isn’t stepping in with the Involuntary Treatment Act to help them.

It’s clear that even some Enumclaw officials agree with Arnold’s neighbors and believe he has little to no control over his actions, which compromises the safety of his community — one of the three requirements Designated Crisis Responders (DCRs) consider when potentially placing someone under civil commitment.

“I believe Arnold does not know how to control his urges,” one Enumclaw police officer wrote in a report. “Based on my conversations with Arnold, I believe he knows full well what he is doing and uses his ‘mental health’ status as an excuse for his behavior.”

Prosecutor Swain said this situation is frustrating, to say the least.

“I always cross my fingers. Maybe he’ll stay. Maybe he’ll finally be put in a facility that is appropriate for him,” she said. “But he always makes his way home to his parents… and we start the cycle all over again.”

Maybe most telling are words from Arnold’s parents.

According to the above police report, Arnold’s father reportedly said that his son is “testing the waters” with his repeated and escalating behavior.

(Father Jonathan does not recall making this statement, and Rosa added that after ten years of her son having these issues, “if a person was to escalate to a more violent nature… then they would have done it by now.”)

“My son is going to die if nothing changes,” Rosa said in a short phone conversation, in regard to alleged death threats from neighbors.

But so far, King County has not moved to civilly commit Arnold for long-term treatment, though he has been civilly committed for short periods of time (from 120 hours or up to two weeks) in the past and has received various forms of outpatient treatment.

… AND WHAT ISN’T?

According to King County Senior Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Anne Mizuta, who is also chair of Involuntary Commitment Unit, the main things DCRs are looking for when deciding if an Involuntary Treatment Act hold is necessary is if a patient is having a behavioral health crisis and is a “serious” threat to themselves, others, or to property due to said crisis.

Most DCR calls do not involve a police arrest or charges for an alleged crime, she added.

If DCRs deem that someone is in crisis and meets that “serious” threat criteria, then the patient can be sent to a treatment facility for up to 120 hours. This initial hold does not have to be approved by a judge, but any continuance of the commitment would need court approval, and the longer the commitment, the more proof is required for a judge to approve the hold.

The bar starts high. Mizuta said a 14-day holds require a “preponderance of evidence” that a patient continues to pose a “serious” risk and that continued treatment is essential to their, or their community’s, health and safety; a 90 or 180-day hold, then, needs be proven by “clear, cogent, and convincing” evidence – the highest standard of proof in civil cases.

Mizuta stressed that while some patients agree to be held for a certain number of days, many do not, and if a facility determines a patient is no longer a “serious” threat to themselves, others, or property, the facility must release them, even if that hold period is not over.

Those that do agree to stay for an entire hold period, or those that facilities determine continue to meet Involuntary Treatment Act criteria for an entire hold period, also retain the right to have a judge review their involuntary treatment status once their hold is completed.

That’s the ITA process in a nutshell, and it has not generally applied to Arnold for two reasons.

First, there is a stringent state-set timeline to follow.

According to his 2023 mental health competency report, Arnold “responds gradually” to medication, but he would not likely become competent to stand trial within the 29-day time frame allotted for those charged with misdemeanors (those charged with felonies have a longer time frame to recover competency). DCRs do not evaluate competency for court.

As such, the report did not recommend Arnold be held for those 29 days, since he would still be unable to stand trial after he was released.

Second, it does not appear Arnold’s repeated actions meet the bar for being a “serious” threat.

Suntop residents and Swain think that Arnold is a danger, especially to local women. Swain said “it [is] just a matter of time” before he escalates, but at this point, her hands are tied.

“I have zero choice, I have no option available to me, except to dismiss the case, because I cannot proceed in a criminal action against someone who is not competent,” Swain said. “And this is where the frustration lies, because he is clearly a danger to the public.”

But it doesn’t appear the King County’s Department of Community And Human Services (which runs the DCR program) or Washington state agree.

On the county level, Mizuta said that DCRs weigh intruding on someone’s life and taking away their civil rights very heavily against civil liberties and the negative impacts an ITA hold can have on their life.

They are “some of the most protective of patient liberties. They’re not going in and just saying, ‘This person needs help and therefore I am putting them in the hospital,’” she added. “I think that the DCRs really only file the initial petition… on those people that they feel are so sick that they absolutely require this for their own health and safety or for community safety.”

And on the state level, Mizuta pointed to RCW 71.05.020, which defines “a likelihood of serious harm” as threats or attempts at self harm or suicide; physical harm against others “as evidenced by behavior which has caused such harm or which places another person… in reasonable fear of sustaining such harm”; or a threat of harm to property, as evidenced by prior substantial loss or damage to property in the past.

So despite the sexual nature of Arnold’s alleged misdemeanors and his repeated behavior, the fact that he has rarely made any major physical contact with purported victims — there was one incident in 2018 where he allegedly attempted to take off a woman’s pants, and one local woman involved in the May 2021 incident said he grabbed her arm while “fumbling” with his shorts — appears to further exclude him from being civilly committed for any sustained length of time.

At the end of the day, it appears that this Suntop community is stuck in a cycle of offense, arrest, release, and neighbors are worried that it’ll take a serious crime for King County to take Arnold seriously. And by then, it’s too late.

“Nobody wants that next step,” one neighbor said.

Still, at least one person is hoping to take next steps to find “… justice for the trauma and undue hardship placed upon myself, my family, and other victims due to the negligence of the state, court system and mental health system.”

IS THE ITA SYSTEM ‘BROKEN’?

The situation Swain finds herself in with Arnold is not the only one she has to deal with, and she holds that this is just one part of a broken mental health system in King County.

“We have lots of people like Jonathan Arnold who are committing offenses and then they’re dismissed after a couple of weeks because they’re not able to proceed — they’re not competent — and [DCRs believe] they’re not a danger to themselves or others,” she said.

But Mizuta believes that the ITA works well — it’s what comes after, or rather, doesn’t come after, that’s the problem.

For example, in most civil commitment cases where the patient is not arrested for a crime and trial competency is not an issue, they often get released as soon as they are no longer a “serious” threat without a stable plan or ability to receive continued treatment.

“The problem is we don’t have a lot of resources when somebody is stable and discharged… sometimes it seems like we work really hard for a patient in crisis and get them just stable enough where they no longer meet criteria, and then they’re discharged free and clear without having the treatments set up to keep them from decompensating to the point that brought them in the hospital in the first place,” Mizuta said.

That’s what the system needs, she continued — not an expanded definition of who can be civilly committed under ITA, but a middle ground for those who don’t meet the current, stringent criteria.

“I can understand [Swain’s] frustration. I hear that frustration from a lot of different sources, not just from the prosecutor perspective, but from people in the community who are very frustrated,” Mizuta said. “There are certainly a lot of people who fall in the place where they may not have the insight to get treatment, which would help them, and they aren’t impaired enough that we can force involuntary treatment on them.”

Mizuta expressed hope that the recently-passed King County Crisis Care Centers Levy, which will generate $1.9 billion in the next nine years to build five new crisis care centers to help people in crisis and preserve and restore long-term treatment beds, will help situations like this.

“Those are all steps in the right direction to provide people more resources,” Mizuta said.

As it stands, King County’s DCR team provides assessments at any hour, any day, all year long; most shifts are five days long, but there are also staff members on-call outside regular work hours and weekends, according to Katie Rogers, King County Department of Community and Human Services’ communication’s director. There are 46 staff members of “differing levels”, and shifts are covered from between 12 to 20 people every week.

DCRs are required by law to respond to requests from hospitals and jails first before community calls.

“Wait times for members of the community can average 11 days,” Rogers said. “This average can be attributed to ongoing issues related to the pandemic, staffing shortages, and changes to state law through HB 1310 and HB 1735.”

“Chronic underfunding of human services, staffing shortages, and varying policies by jurisdiction” also delays response time, she continued.

DCRs complete an average of two cases a day, and “the time spent on each case could be several hours,” Rogers said, noting that DCRs review past cases in their records, contact witnesses, treatment providers, and the patient in that time, if possible.

Rogers said that while DCRs work as fast as they can, “chronic underfunding of human services, staffing shortages, and varying policies by jurisdiction” delays response time.