Congressmembers, Tribal leaders and dozens more local leaders gathered at the Howard Hanson Dam Tuesday of last week to celebrate the revival of the decades-delayed project to return salmon to the Green River’s upper watershed.

The stakeholders assembled Aug. 30 to answer press questions at the dam, which holds back the Howard Hanson Reservoir at Eagle Gorge.

The $855 million project will reintroduce endangered salmon into their historical habitat, helping the iconic fish boost their numbers and viability. That, in turn, will restore food for wildlife like bears, eagles and endangered orcas, and help fulfill the United States’ obligations to tribes like the Muckleshoot to provide access to fishing and hunting.

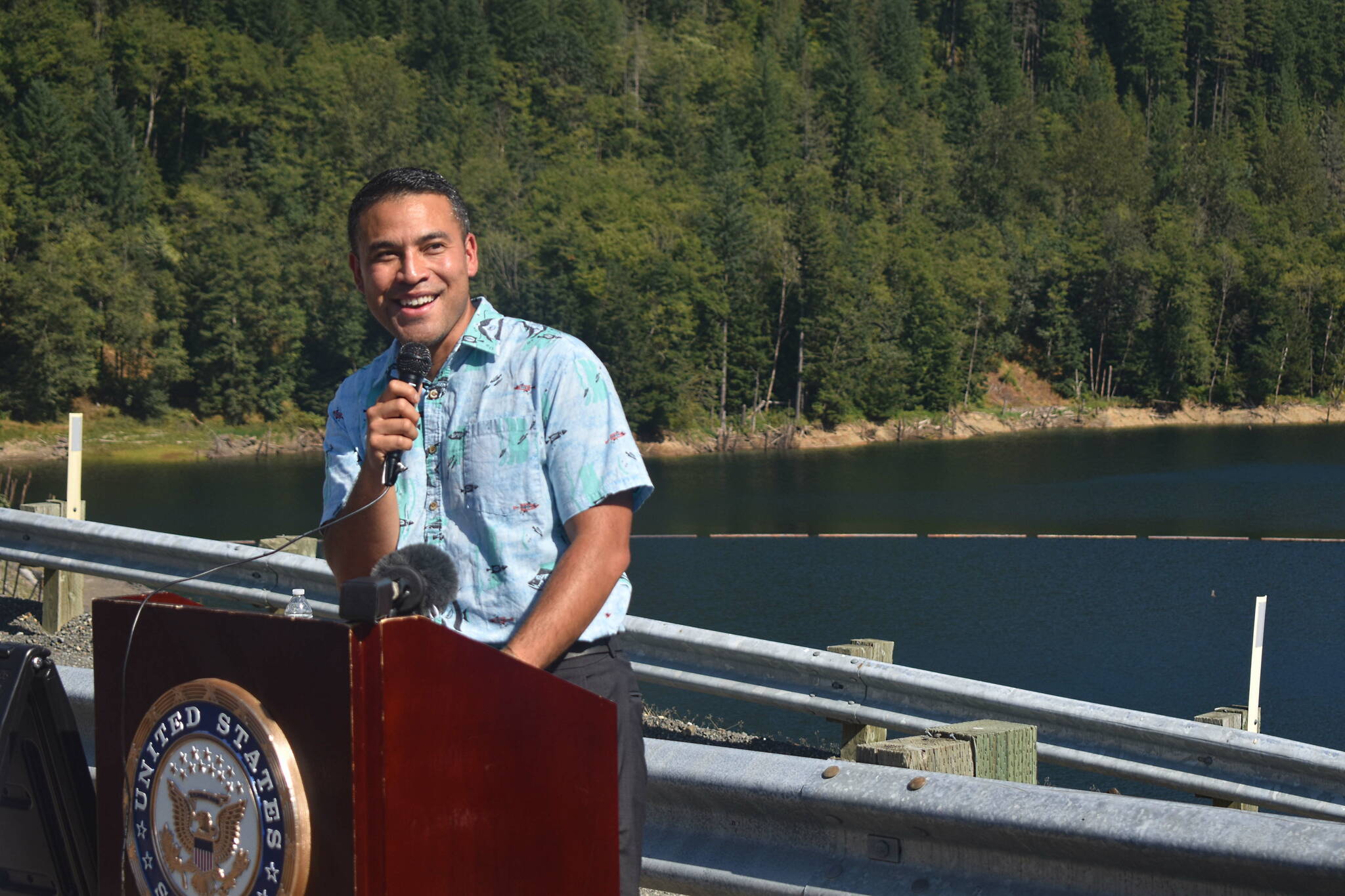

Muckleshoot Tribal Council Chair Jaison Elkins thanked Senator Patty Murray and Representative Dr. Kim Schrier for their work on behalf of the project and shared the value that a vital salmon population holds for the tribe.

“The Muckleshoot people are salmon people,” Elkins said. “Salmon provide physical, cultural and spiritual sustenance to us … and that is why I’m here today to support and protect the future salmon runs.”

The Muckleshoot possess rights under two treaties with the United States: The Treaty of Medicine Creek, signed in 1854, and the Treaty of Point Elliott, signed in 1855, which among other things recognized and guaranteed traditional hunting and fishing rights for several tribes in the Puget Sound area in exchange for millions of acres of territory. The Muckleshoot Reservation was established in 1857.

“It seems like something the federal government should uphold,” Elkins said. “To let us be Indians. To live a good life. … Despite the assurances in the treaties, our rights have always been threatened by changing climate, man-made impediments to spawning, such as dams, and the lack of federal investment in preserving and protecting our fish runs. The right to fish, which our ancestors fought so hard to protect, is meaningless if there’s no fish in the rivers.”

The fish passage project secured a $220 million shot in the arm this spring, negotiated by Washington’s congressmembers, as part of the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill approved by Congress and signed by President Joe Biden last year. Sen. Patty Murray (D) has advocated for the project for years, securing $44 million for repairs at the dam in 2010.

“We’re talking about opening up 100 more miles of salmon habitat thanks to the fish passage we’re creating here,” Murray said. “That funding was only made possible because we passed the bipartisan infrastructure law.”

The project could receive another chunk of cash through the Water Resources Development Act, passed last month by the U.S. Senate. Both houses will have to pass the bill for it to become law.

The project will be built by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, but it has been shaped with the help of many groups, including the Tribes. Jaime Pinkham, the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, lauded that collaboration.

“The Tribes helped to design and operate fish passage facilities on these waters and rivers, (and) that is just a change in how we’ve worked in the past,” Pinkham said. “The lessons we’ve learned at Mud Mountain (Dam), we’ve learned together with the Tribes.”

The Tribes were at the table for decision-making both in a legal, political, environmental and scientific sense, Pinkham said, rather than relegated to watch from the sidelines.

“When the Army Corps of Engineers looked for help on how to design the fish passage facility at Mud Mountain Dam, they didn’t have to look far,” Pinkham said. “They could look to the capacity the Tribes built, the expertise. So you’re seeing the Tribes coming together not just as passive beneficiaries of the fisheries, but as active managers. And that’s a change.”

ABOUT THE PROJECT

The Howard Hanson Dam and its smaller diversion dam three miles downstream were built in 1962 and 1912, respectively, to restrain frequent flooding over the Green River Valley and to bank water to augment the river in the dry season. The diversion dam also provides drinking water for the Tacoma area.

The dams accomplished all those goals, but at a steep cost: Migrating salmon and steelhead, seeking their ancestral spawning grounds in Eagle Gorge, are now met with a gray concrete wall. The fish species have suffered huge declines in their populations due to habitat loss, climate change and environmental pollution.

Locked behind the Howard Hanson lies more than 100 more miles of high-quality spawning and rearing habitat for fish in the river’s watershed, largely unspoiled by human development.

Unlocking that upper watershed above that dam to fish would be a game-changer for the threatened Puget Sound Chinook salmon and steelhead, scientists at NOAA said. And the fate of those fish is intertwined with the endangered Southern resident killer whales, or Orcas, which feed on the fish.

The watershed is extremely valuable to all the fish that could use it, but especially the steelhead and Coho salmon, which travel further upriver than their Chinook and Chum cousins.

The Howard Hanson project, authorized by Congress in 1999, sought to both increase the dam’s water storage to the tune of more than 30,000 acre-feet, which would aid its flood control and water management abilities, and to improve the prospects for fish in the river by giving them a way through the dams. But it ground to a halt around a decade ago when the projected costs started exceeding congressionally authorizing funding limits.

In 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ordered the Corps to figure it out and finish the fish passage facility no later than 2030. A year later, all of Washington state’s congressmembers came together to formally call upon the Army Corps to prioritize salmon passage at the dam.

Tacoma Public Utilities already have a trap-and-haul system operational to bring the fish up past both dams, and they can get the fish back down the diversion dam. The only problem left is that fish can’t yet swim down from the main dam, due in part to a tricky engineering challenge.

The Howard Hanson Dam’s water level fluctuates by more than 100 feet depending on the season and weather. A tunnel at the bottom of the dam theoretically allows passage, but salmon like to swim near the top of the water, and diving that deep to find the passage goes against their hardwired instincts.

So the new design will meet the fishes more than halfway — literally. Engineers will construct five large openings to the tunnel, stacked one-on-top-the-other, so that the fish always have an entry point no matter where the surface of the water sits. That’s what engineers hope to have completed by 2030.

If all goes to plan this time, the Corps will have a design done in three and a half years, and after that, only another four years of construction. The good news is that much of the water storage work is already done, and once the fish passage facility is done the Corps plans to add even more water storage to the dam.