It’s 11 a.m. Pacific Time, but my body still feels like it’s 3 a.m. I have a sore throat, I’m coughing, and I am filled with dread: Oh no, after all this hard work to finally get back home… do I have COVID? Okay, maybe I do have COVID. That’s no big deal. I just got my booster and I can get a test… right? Wait, how do you get a test? I took a PCR test for my flight but how do I get an antigen test? I have no idea what to do.

I have my husband ask his dad if he knows where we can get a quick test. We get tossed a test like it’s a snack-size bag of chips from Costco and I’m completely bewildered, like a prisoner in jail getting tossed a key to my cell.

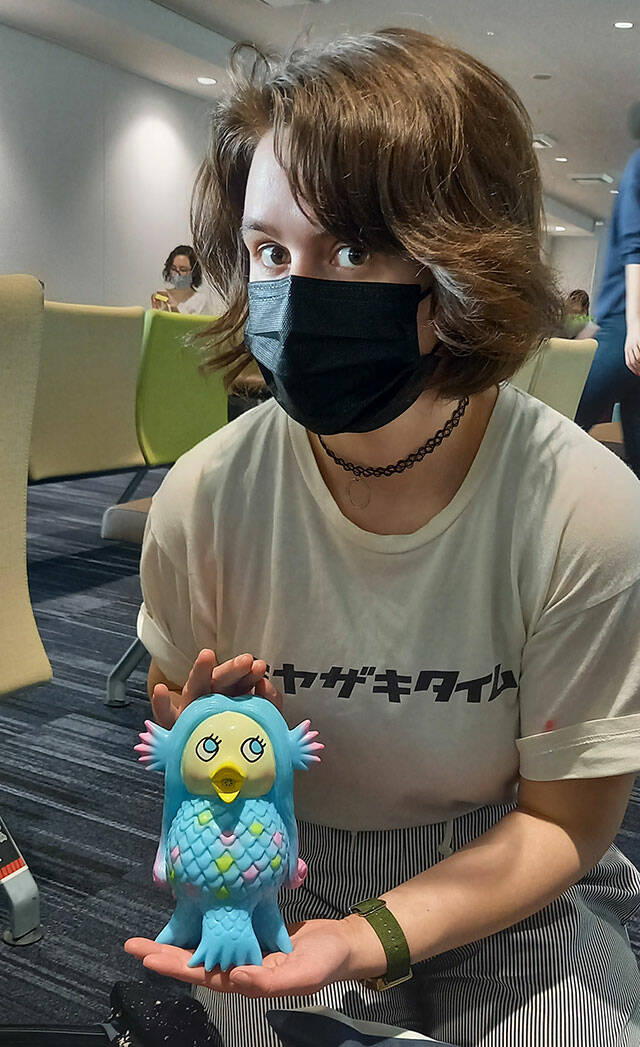

Yeah, you might be reading this and thinking “who is this idiot who’s been living under a rock, not knowing how to get a quick COVID test?” Well, this is an idiot who, up until recently, had been living in Japan throughout the entire pandemic, and let me tell you — COVID-19 has been a completely different ball game over there.

Until this spring — a little over two years into the pandemic — I had been living in southern Japan for close to five years, working as an Assistant Language Teacher and a freelance writer. I was in a rural prefecture called Miyazaki which didn’t have its first reported case until July 29, 2020, almost five months after the first reported case in the entire country.

Due to Japan’s constitution, the government doesn’t have the power or will to impose strict lockdowns like in other countries. Instead, the government passed the responsibility on to local governments and to the people, so cities and prefectures created their own guidelines. Some of the guidelines were based on common sense, like wearing masks (something that was already the norm in Japanese society) and social distancing, while others were nonsensical and sometimes downright xenophobic, like a health center in Ibaraki telling people not to eat dinner with foreigners.

Where I lived in Japan, basically all public events were canceled for 2020, restaurants closed really early, and mask-wearing in public was strongly encouraged, which seemed to keep our numbers low. However, mass testing was basically non-existent. At one point, early in the pandemic, I became extremely ill and needed to go to the hospital twice. I had some of the symptoms of the coronavirus but I didn’t have them all so, when I asked to be tested for COVID-19, they refused on the grounds that I didn’t have a fever. This development seemed very suspicious and as it made everyone wary of the data and extra cautious.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what could be the reason for Japan’s relative “success” but for many of us living in Japan at the height of the pandemic, it seemed a lot like dumb luck mixed with the aforementioned caution. People in our part of Japan were taking the coronavirus very seriously and there was a real obligation to do what needed to be done for the greater good.

As we all read the news and listened to stories from our friends and families outside of Japan, we felt extremely fortunate — sure, the Japanese government wasn’t doing much but at least people were figuratively coming together and doing what was right for the community. Everything about the high COVID cases, the avoidable deaths, and the perplexing anti-mask protests in the U.S. made me extremely anxious at the prospect of returning home.

And you can imagine my shock upon landing back in Washington and re-acclimating myself to life in America. Omicron hadn’t quite made its way to my neck of the woods in rural Japan before I had left but I at least had an idea from what my friends had told me. Despite this, it still made me do a few double-takes when I saw un-masked Washingtonians out and about in public, acting like nothing was happening.

It was jarring and it made me cautious in a way that I hadn’t been throughout the first two years of the pandemic — instead of being part of a collective that was trying to keep COVID at bay, it felt like there was damage in the hull of a ship and someone had screamed “every man for himself!” It took quite some time to get used to how things are handled here in south King County but I’m thankful that the people I surround myself with still take it seriously.

In the weeks since my homecoming, I’ve come to terms with the enormous differences in attitudes and precautions that are made here in the U.S. but I’ve also discovered that, after a while, the shock has worn off. I think getting a negative on my first antigen test helped with that.

Bailey Jo Josie is a reporter with the Federal Way Mirror. She can be contacted at bailey.jo.josie@fedwaymirror.com.